Lancashire’s Medieval Anchorites

By Dr Emma Nuding

From A Room of One’s Own to I’m an Anchorite, Get Me Out of Here!

.jpg)

In late medieval England, there was a curious group of people who chose to withdraw completely from society and live as religious recluses; they gave up their families and friends, and their creature comforts, and vowed to never leave a small room – which was sometimes dramatically bricked-up after they entered. Unlike monks and nuns, they couldn’t even move around a monastery grounds. To all intents and purposes, these people were ‘dead to the world’, a fact that their initiation rite stressed through its use of the funeral liturgy and its recommendation that the would-be recluse crawled into a mock grave and was sprinkled with ashes. These people were called ancres or anchorites, and while they could technically included men as well as women, the practice seems to have been associated more with women than men by the late medieval period. Indeed, the most well-known examples of anchorites today are women, such as St Julian of Norwich.

Medieval Lancashire had its female anchorites just as medieval Norfolk did, and – unusually – the stories of two of them from the 1400s have been preserved: Agnes Schepard (or Shepherd) of Pilling, and Isolde Heton of Whalley. You might be wondering how these women came to be enclosed, and whether they regretted it: read on to find out.

As modern audiences, we might assume that female anchorites were forced into seclusion. However, there was probably some element of active choice on the anchorite’s part (even if an active choice within a limited menu of options): it was actually quite a difficult process to become an anchorite, and it was something of an elite position. You had to get formal backing from a bishop and you either had to have wealth yourself to pay for your provisions while enclosed, or you had to secure the support of a wealthy patron who would pay for them. Therefore, would-be anchorites had to lay out a case for why they should be taken on and why they wouldn’t become a liability to the organisation (usually either a parish church or a chapel ran by a religious community) which they were attached to.

According to one anonymous fifteenth-century writer, there were some excellent reasons for becoming an anchorite: penance for sins and quiet contemplation of the divine. This writer also mentioned what he considered to be a very poor reason for becoming an anchorite: it offered people an easier life. This might sound surprising, but we should consider that being an anchorite allowed women a relatively large amount of leisure time. This could be used for approved activities like needlework but also lots of reading, as well as copying and illuminating manuscripts – contrary to popular belief, many elite women in the later Middle Ages could read and some could also write. As an anchorite, you would also be spared some other challenging tasks, whether running a large household or rearing children, and you would be spared the dangers of childbirth. Like monks and nuns, you would have to pray at all hours of the night, but your prayers were shorter and less intense. Circulating in the period were many strict guidebooks (probably written by men) about the lives female anchorites should lead, but we don’t know to what extent enclosed women actually compiled with all these rules: it probably varied, and besides, who was checking what happened within the anchorhold itself?

Because an anchorite was, to some extent, the master of her house, the king of her castle: she was allowed up to two servants to help her, and she was their leader and spiritual guide. Some anchorites also became people of local importance (perhaps with a touch of celebrity) as they received visitors who sought out their advice and counsel, probably whispered through a shuttered internal window. While anchorites ate a plain diet of bread, vegetable stew and fish, they certainly weren’t encouraged to starve themselves. Similarly, they were allowed to heat their cells with peat fires and to light it with oil lamps during the night. Some anchorites even had a garden for growing food attached to their cell, though it is unclear whether they would have had a window which looked out onto it. A ‘squint’ window inside the cell would have looked onto the altar in the adjoining church, angled so the anchorite could see out but no one else could see in. These women clearly led a quiet life, but (as the modern interest in mindfulness, retreats and wellness testifies to) there must have been lots to value within that simpler way of living. Occasionally, however, it seems that for some anchorites, the peacefulness of the anchorhold couldn’t compete with the calls of the world outside of it.

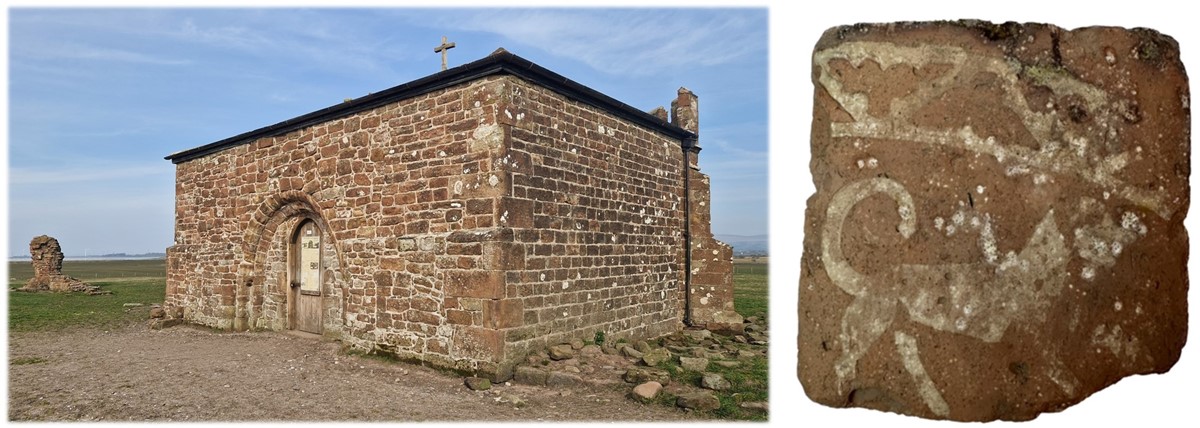

Our first Lancashire Anchorite is Agnes Schepard. She started off life as a nun in the community of Norton Priory, the remains of which still exist just south of Warrington. Clearly, something about the communal religious life wasn’t suiting Agnes, because in 1493 the bishop of Lichfield asked for her to be allowed to leave her sisters and become a solitary anchoress at a chapel in Pilling, a small settlement about ten miles south of Lancaster along the coast. The bishop was writing to the canons of Cockersand Abbey, who ran the chapel there as part of the pastoral services they offered to the local community: the canons were no doubt fans of religious seclusion as their abbey was built on the site of the twelfth-century cell of another religious solitary, Hugh Garth. The remains of Cockersand Abbey itself (1) can still be seen south of Glasson Dock, and Lancaster City Museum has some patterned tiles from the site on display in the first-floor galleries (2).

You can’t visit the remains of Agnes’s anchorhold at Pilling however: neither it nor the chapel it was attached to have survived, though a local dig in the 1950s uncovered the chapel’s foundations and the altar stone that Agnes may have looked out onto from her squint (current whereabouts unknown). By the Georgian period, these buildings had fallen into disrepair and a different chapel (3) was built about a mile to the west, closer to parishioners, and further from the marsh.

If you visited Pilling in the 1400s, you would find a particularly flat and bleak setting in which to set up shop as an anchoress. There wouldn’t have been much to see apart from salt marsh and mud flats; Agnes’ anchorhold would have been battered by the elements and surrounded by floods, all of which would have limited the flow of visitors and provisions. (4)

Curiously, this is probably why a holy woman like Agnes wanted to be there: desolate landscapes like these have been favoured by religious solitaries through time, whether desert fathers like St Anthony, or saints of the British Isles like St Guthlac of Crowland who settled on the marshy flats of the Lincolnshire fens in the eighth century. Places like Pilling and Crowland were lacking in social and cultural opportunities, but they could offer rich spiritual ones which more than made up for the loss.

We don’t know why Agnes chose this lifestyle (assuming it wasn’t chosen for her) but we do know that when she became an anchorite, she was already a nun. Furthermore, the accounts of Cockersand Abbey show that she was still living in the anchorhold eight years after she was first enclosed, and they offer the tantalizing suggestion that she was paying her own way. Therefore, we can speculate that Agnes was genuinely attracted to the rigours of the anchoritic life and that she did really want the spiritual experience that being enclosed in an isolated spot would bring: that was how she found herself in 1493 quietly contemplating the flooded marshes around Pilling, about to enter her little cell, her own Lancashire island-paradise.

Our second Lancashire anchorite is Isolde Heton, a woman who was enclosed in 1437 in the anchorhold attached to the parish church at Whalley, a medieval town between Blackburn and Clitheroe (5). We know that Isolde was a widow by the time she became an anchoress and that she was from Lancashire: her surname might indicate that she was from Heaton near Bolton. Isolde hailed from an affluent social group called the gentry which was a relatively well-off land-owning middle class (including commoners and minor aristocrats) that arose in the late Middle Ages.

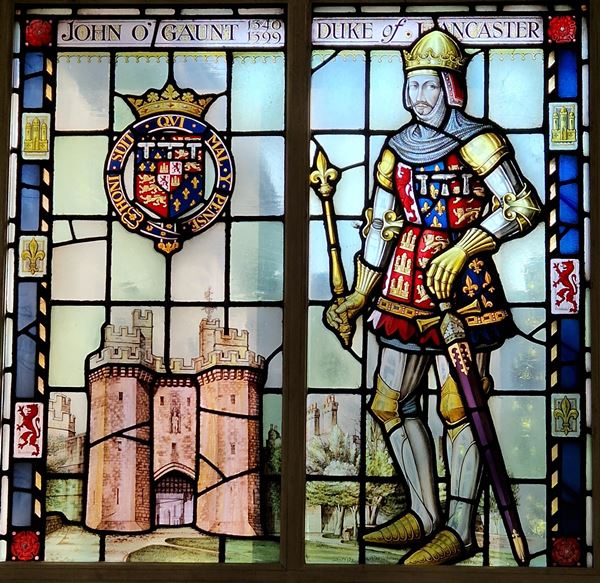

Isolde’s anchorhold was maintained by, and immediately next door to, what would become the richest monastic house in Lancashire at the Dissolution: Whalley Abbey (6). The anchorhold had been at Whalley since 1349 when it was established (with generous provision) by Henry Duke of Lancaster, the father of Blanche of Lancaster, who later married John of Gaunt, arguably the most famous medieval figure associated with Lancaster itself (7). You can still visit Whalley’s parish church, as well as the abbey ruins, but there is no trace of Isolde’s own anchorhold – possibly indicating that it was built with wood rather than stone.

Another possible reason for why there is no trace of Isolde’s anchorhold is simply that it stopped being used and fell into disrepair: Isolde was famously the ‘last anchorite of Whalley’. Her actions (combined with those of the monks who were meant to be hosting her) meant that there would never again be an anchorite on the site. Was this because Isolde was a fake, an unholy holy woman? Nineteenth-century historians such as Thomas Whitaker, looking at Isolde’s case with a hefty dose of misogyny, seemed to think so. However, the truth is likely more complex: Isolde may have been genuinely attracted to the anchoritic life, but the demands of her previous family life ultimately overrode her religious vocation.

A Family Left Behind

The truth is that when Isolde became an anchoress, she wasn’t just a widow but the mother of four children young enough to need parental care and guidance: a ten-year-old heir called William as well as his younger brother and two sisters. We might be surprised that Isolde left her young children at home unparented to become an anchoress: perhaps having her own living provided for by the royal endowment of the anchorage improved the family fortunes overall. In the Middle Ages, it was also more normal for elite families to send their children away to grow up in other people’s households than it is today. Whether or not we would approve of Isolde’s choice to physically leave her family, it is important to note that she didn’t stop being a mother even in the anchorhold: she clearly kept in touch with her children.

We know this because of something that happened in Isolde’s absence that forced her intervention: about five or six years after she was first enclosed, Isolde’s wider family agreed to marry her son William to the daughter of a local landowner for a modest amount of money, an arrangement that Isolde felt wasn’t enough to provide for all the siblings. As a consequence, Isolde penned a petition (probably dictated to her serving woman at the anchorage) pleading with the officials of the realm to intervene on her behalf, claiming that she had already secured a better match for her son. The petition is a finely crafted piece of persuasive writing: Isolde paints herself as a vulnerable holy woman, employed (no less) in the King’s own service, and points out that the local landowner took advantage of the fact that she was enclosed to arrange the marriage behind her back. Isolde was clearly wilier than your average living corpse.

The Plot Thickens…

Indeed, Isolde didn’t confine herself to writing strongly worded letters from afar: a second petition written by the landowner in question suggests that Isolde actually broke her vows at some point and left her anchorage to physically go and intervene in the situation, absconding with her son so that he couldn’t be married off. Maybe Isolde intended to go back to the anchorage; maybe she had had enough.

Meanwhile, the Whalley monks (who seemed to have come to resent the anchoress and her servants and their need for provisions, and were no doubt suspicious of women in general given their strict vows) took the opportunity to petition the authorities themselves to dismantle the anchorhold completely: they complained that Isolde had departed her cell ‘contrary to her own oath and profession’ and that she was ‘not willing […] to be restored again.’ They also complained that Isolde had ‘misgoverned’ the women attending her with the result that some of them had actually become ‘with child’ in the ‘hallowed place’ of the anchorhold itself. Who knows if the second accusation was true – but it certainly had the intended effect.

So, what happened?

The Whalley monks got their wish: the anchorage was closed by the King in 1443. We don’t know whether Isolde got her wish as well: the historical record is silent about what happened to her, whether she able to secure a more advantageous match for her son, or whether she continued a religious vocation away from her anchorhold in a different form. My guess is that she would have been a great candidate for the ‘middle way’, a path which combined religious vocation and family life, initially popularised by the fourteenth-century mystic Walter Hilton and increasingly in vogue in the Isolde’s own time.

However, what we do know is that because Isolde continued to play a role in her family affairs (despite supposedly being dead to the world), she contributed to the end of the century-long tradition of Whalley Abbey having a female anchorite attached to it: she might have genuinely been attracted to the anchoritic life, but she wasn’t able to completely devote herself to a life of contemplation; she saw herself as mother and the leader of a household at the same time as being an anchoress, and ultimately that dual-role proved incompatible. Isolde couldn’t have her cake and eat it too.

Having heard about our two Lancashire anchorites, we might wonder whether Agnes and Isolde had different reasons for enclosing themselves, and whether they lived to regret it to an equal degree. Perhaps for Agnes, the anchorhold provided (to misquote Virginia Woolf) a ‘cell of one’s own’ offering solitude, contemplation and the opportunity to read and work within the parameters of a simpler life away from the noise of the world, sequestered deep in the marshes. Perhaps something like that was initially true for Isolde within the relatively cushier environs of Whalley Abbey. However, when the mother of four was faced with a mounting family crisis, she clearly opened the shutters, knocked down the walls and shouted to anyone that would hear: ‘I’m an anchorite: get me out of here!’.

- Anon., ‘The Last Ancress of Whalley’, Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire 64 (1912): 268–72

- E. A. Jones, Hermits and Anchorites in England, 1200-1550 (Manchester University Press, 2019)

- Rentale de Cockersand, ed. F. R. Raines (Chetham Society, 1861)

- W. Headlie Lawrenson, ‘Pilling’s First Church’, The Over-Wyre Historical Journal, 1 (1980), https://www.wyrearchaeology.org.uk/index.php/resources/pilling-historical-society?view=article&id=700 [accessed 21 March 2025]

- Thomas Whitaker, An History of the Original Parish of Whalley (Nichols, 1872)

- 'Townships: Pilling', in A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 7, ed. William Farrer, J. Brownbill (London, 1912), British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol7/pp332-335 [accessed 18 March 2025]

- 'The parish of Whalley', in A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 6, ed. William Farrer, J. Brownbill (London, 1911), British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol6/pp349-360 [accessed 7 April 2025].